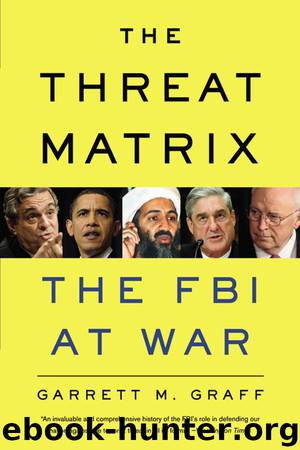

The Threat Matrix: The FBI at War in the Age of Global Terror by Garrett M. Graff

Author:Garrett M. Graff [Graff, Garrett M.]

Language: eng

Format: epub, azw3, mobi

ISBN: 9780316120883

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2011-03-28T00:00:00+00:00

President Bush’s November 13, 2001, order, “Detention, Treatment, and Trial of Certain Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism,” was, depending on one’s viewpoint, either a terribly crafted or a perfectly written document. Filled with ambiguity and as broad as the Potomac River, the order had no checks, balances, or safeguards. It effectively meant that the Department of Defense could do whatever it wanted. How that would play out on the ground became one of the defining battles of the post-9/11 world. The first question posed by the president’s order was where prisoners captured in the war on terror would go. To the interagency group studying the question, it was clear that the continental United States—“CONUS” in military and Bureau parlance—was out of the question for political reasons, even before it was ruled out on legal grounds. During the brainstorming sessions, it was someone from the Department of Justice who first said, “What about Guantánamo?” The military base on the southeastern tip of Cuba seemed to fit Secretary Rumsfeld’s condition of “the legal equivalent of outer space” perfectly. About two thirds the size of the District of Columbia, Guantánamo was separated from the Cuban nation by miles of fence, barbed wire, and, on the Cuban side, a minefield. It was the modern-day equivalent of Alcatraz, the twenty-first century’s inescapable “rock.” The oldest overseas base in the U.S. military, leased from the Cuban government in near perpetuity for about $4,000 annually (not that Castro had cashed a rent check in decades), Guantánamo Bay had twice served in the past decade as a legal no-man’s-land. During crises in Haiti and Cuba, tens of thousands of fleeing Haitians and Cubans picked up at sea by the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Coast Guard had lived for extended periods of time on the base in “migrant” camps (the Defense Department had gone out of its way to ensure that they were called “migrants” rather than “refugees” to limit their legal options in the United States). One of the camps, which had been named using NATO’s phonetic alphabet as Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, and so on, had been designated for the migrants who had a violent streak, the criminals: Camp X-Ray. Its forty open-air fenced pens still stood on a corner of the sprawling fifty-four-square-mile base.

The military announced on December 27, 2001, two days after Christmas, that the first detainees from the battlefields in Afghanistan would arrive at “Gitmo” within weeks. Air Force General Richard B. Myers said the first wave would include eight detainees from the USS Peleliu and thirty-seven more from the “high-value detainee” camp near the Kandahar airport. The following day, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel filed an opinion providing the legal underpinning for the camp: Deputy Assistant Attorneys General Patrick Philbin and John Yoo wrote that Gitmo was outside of the purview of U.S. courts. Ten days later, on January 8, 2002, Robert Mueller’s high school classmate Will Taft, the general counsel of the State Department, walked out of a White House briefing on the rules of Guantánamo and turned to his aides: “We’ve got trouble.

Download

The Threat Matrix: The FBI at War in the Age of Global Terror by Garrett M. Graff.azw3

The Threat Matrix: The FBI at War in the Age of Global Terror by Garrett M. Graff.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16681)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11495)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7810)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5805)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5058)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4841)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4796)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4462)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4446)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4430)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4426)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4357)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4095)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4045)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4028)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3900)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3884)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3793)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3743)